The conference took place in the Andrássy Hall of Andrássy University Budapest as part of the „Changing Orders Research Programme.“ Divided into three panels, the neutrality of various countries from Central Europe, Western Europe, and Southeastern Europe was examined. The conference was organized by Dr. András Hettyey, Associate Professor at AUB.

Dr. habil. Orsolya Tamássy-Lénart, Vice Rector for Academic Affairs and Students at AUB, and Dr. András Hettyey welcomed the audience and introduced the event. Following this, Dr. Hettyey opened the event with a kick-off presentation, raising critical questions about neutrality in light of recent literature and highlighting publication opportunities in the context of the programme.

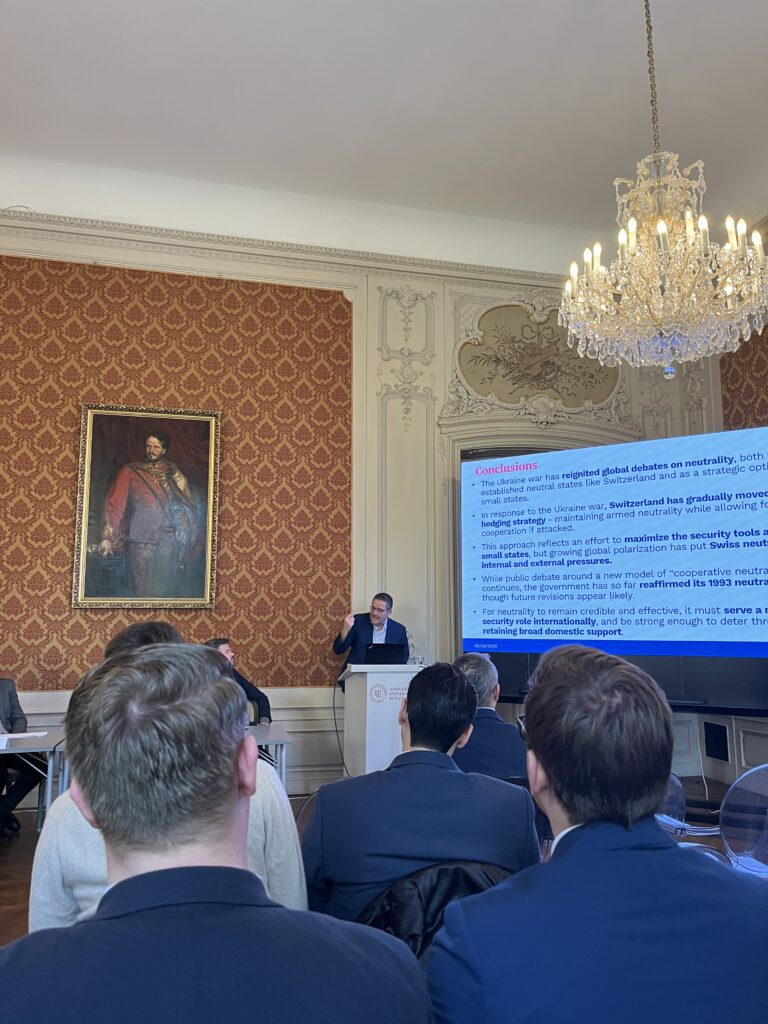

Jean-Marc Rickli of the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) opened the first panel with a presentation on Swiss neutrality. He highlighted that in the past, neutrality primarily served to protect national independence and entailed a clear distance from military alliances, a view that was particularly pronounced during the Cold War. After 1990, the concept shifted toward an active, mediating neutrality, in which Switzerland acted as a bridge-builder and partner in international peace processes. The war in Ukraine put this position to the test: on the one hand, the importance of territorial defense was reemphasized, while on the other, Switzerland consistently maintained its ban on arms exports. Today, Swiss neutrality finds itself caught in the tension between historical continuity, new global conflicts, and domestic political initiatives to reinterpret the concept of neutrality.

The next lecture was given by Christoph Schwarz from the Austria Institute for European and Security Policy (AIES) on Austria’s neutrality since 1955, in which he demonstrated how neutrality has changed over time. This ranged from the phase of consolidation to the current phase of stagnation and Europeanization. The focus of the presentation was the tension between Austrian neutrality and EU membership, particularly with regard to mutual assistance obligations. Russia’s war against Ukraine represented a turning point in which neutrality became increasingly politicized again, although its practical interpretation changed little. Finally, survey results were presented, providing insights into current opinions and controversies surrounding the role of Austrian neutrality.

The final presentation of this panel was given by Tamás Baranyi from the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs. He began by explaining that Hungary does not pursue a neutral foreign policy and clearly aligns itself with the West, especially NATO. While there was a symbolic declaration of neutrality in 1956, according to Baranyi, this had no long-term significance. He pointed out that Hungary cannot afford a neutral position due to its geographical location and numerous international ties. The presentation also addressed the fact that Hungary has opened up economically to investment, remained pro-Western in security policy, and has not participated militarily, including in the war in Ukraine. Hungary’s neutrality was presented as a theoretical idea, but the focus is on protecting national security and economic interests.

The second panel was opened by Douglas Brommesson from Linnaeus University in Växjö, Sweden. He discussed Sweden’s neutrality over the past 200 years and identified characteristics of its neutrality policy. Dr. Brommesson emphasized that the policy of neutrality and its implementation have always been a voluntary decision on the part of Sweden. The policy of neutrality was also linked to a strong national defense, as Sweden possessed the fifth largest air force in the world in the 1950s. In recent decades, a gradual process has led away from the policy of neutrality, until the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine in 2022 provided the final impetus for the final abandonment of neutrality. However, the post-neutral identity is still present in some ways in the country.

Following this, Dr. Mariano Barbato, DAAD long-term lecturer at the Chair of Comparative Politics at the AUB, spoke about permanent neutrality as both a price and a path for the Vatican. He dealt with the Lateran Treaty of 1929 and the associated international legal and historical significance of the Lateran Treaty between the Holy See and Italy. The focus was also on Article 24, which stipulates the permanent neutrality of the Holy See in secular affairs and temporary rivalries, while simultaneously granting the right to exercise its moral and spiritual authority. Barbato’s lecture emphasized that the Lateran Treaty settled the long-standing Roman Question. It was a modest price to pay for peace agreements, thus also serving as the foundation for the Vatican’s permanent neutrality and moral influence, which continue to this day.

Dr. Christina Griessler, associate professor at AUB and the Rector’s Representative for Western Balkan Cooperation, illuminated the historical development of Irish neutrality in her lecture. This is closely linked to Ireland’s quest for independence and its complex relationship with its neighboring United Kingdom. She further explained that this neutrality was made possible, in particular, by British acceptance. Although the 1937 Constitution does not contain a direct reference to it, Ireland has developed an independent policy of neutrality over the decades, as Dr. Griessler explained. Participation in international peacekeeping missions is now a central component of its foreign policy. With the so-called Triple Lock system, Ireland sets strict conditions for the deployment of troops abroad. This neutrality is motivated less by ideology than by pragmatism. Given the geopolitical situation and limited scope for action, Ireland sees itself as a peacemaking, but not an isolationist, actor on the international level.

In the third panel, Natalia Stercul from the State University of Moldova dedicated her presentation to the role of the Republic of Moldova’s neutrality in the context of Euro-Atlantic integration efforts. She emphasized that Moldova is likely to maintain its neutrality despite geopolitical tensions and security challenges. This decision depends significantly on the regional security environment and the progress of the domestic reform process. Stercul emphasized that even neutral states are required to adapt their defense strategies and strengthen security policy structures. Moldova is increasingly developing a security-conscious political culture that questions societal notions of neutrality and adapts them to new conditions. If Moldova joins the EU, it would have to redefine its neutrality within the framework of the common foreign and security policy. The presentation made it clear that neutrality is not a static concept, but rather a flexible security policy strategy.

Dejan Stojkovic, from the Defense University of Belgrade, explained Serbia’s neutrality in more detail. He explained that military neutrality is a conscious security policy decision deeply rooted in historical experiences with violations of sovereignty. Serbia’s neutrality also means refraining from joining military alliances, participating in armed conflicts, and stationing foreign troops. At the same time, Serbia is committed to international partnerships and peacekeeping missions. This model offers advantages such as strategic independence, broad foreign policy flexibility, and national self-determination, but is under growing pressure from geopolitical tensions and the need for independent security. According to Dr. Stojkovic, the majority of the population supports this course.

The final lecture was given by Iuliia Osmolovska, Head of the GLOBESEC Office in Kyiv, on Ukraine’s neutrality. She highlighted the challenges that neutral states face in complex geopolitical situations and argued that neutrality alone does not provide reliable protection, especially when the international legal system is weakened and a larger neighboring state violates its principles. She then outlined the historical development of Ukrainian neutrality, from early independence efforts to legal changes since the 1990s. For decades, Ukraine maintained a position close to neutrality without joining military alliances. However, this stance was not understood as a permanent principle, but rather as a tactical decision. In response to security threats and experiences of military aggression, neutrality was increasingly questioned. She also emphasized that the security policy role of a state is dynamic, as Ukraine, for example, has evolved from a security risk factor to a security enhancer for Europe.